Victims of a war of attrition: The First World War. Douamont

National Cemetery, France, for the victims of the Battle of Verdun

National Cemetery, France, for the victims of the Battle of Verdun

One year ago, the Russia invaded Ukraine under the pretext that it was governed by Nazis. The aim was to topple the government and to change the country into a vassal state, if not to annex parts of it. The Russian leadership – say president Putin – expected that the job could be done within a few weeks. It didn’t happen. Russia completely underestimated the will of the Ukrainian people to resist, the vigour of the its leadership, and the strength of the Ukrainian army. Moreover, Ukraine was from the beginning strongly supported by the Western countries, which were united in their support, unlike what the Russian leadership hoped. The Ukrainian army forced the Russian troops to leave parts of the occupied areas, but the war led to much destruction, human suffering and violation of humanitarian laws. Gradually, the character of the war changed and what had begun as a mobile war turned into a war of attrition. As it looks now, it will remain so for the time to come, and it’s not unlikely that this war will last many years. Sometimes one party will make a step forward, then the other party will, but a military breakthrough is not likely to happen for the time to come. The parties will continue fighting till one of them has become so exhausted that it wants to stop or collapses.

What actually is a war of attrition? In short, it is a military strategy by which you try to wear out the enemy that way that his resources become exhausted, so that he cannot keep up the war. This is usually done by small or sometimes massive attacks, then here, then there, without a big strategic aim. Or rather, exhaustion of the enemy is the strategic aim. The attacks, so it is hoped, will cost the enemy so many troops and military resources (weapons) that in the end they cannot be replaced any longer. Often the aim is not only the destruction of military resources but also the resources of the enemy country as a whole and the will of its people to continue the war. This can involve an economic boycott and destructing the enemy’s infrastructure by bombing roads, power stations, etc. if not its cities. However, by doing so you risk that you’ll also wear out yourself. For being able to destroy your enemy step by step does also cost many resources, and if your enemy is strong, your own resources can become exhausted. Moreover, your enemy can also try to exhaust you.

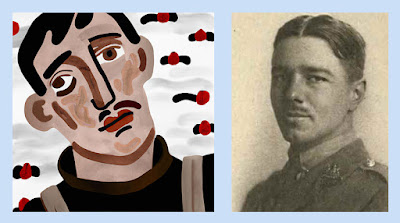

Winning a war by exhausting the enemy has often been tried in history. The best-known case is the First World War (1914-1918) (WW1). When in August 1914 Germany invaded Belgium and France, it thought to win the war quickly, but when it suffered a defeat in the Battle of the Marne, the German military staff saw no other option than to dig in. So the trench war on the Western Front started, and with it the war of attrition. Most of the time the war consisted in small attacks to win a few square metres of land. All attempts to break through the front failed and led to exhausting long-lasting combats. After four years Germany was so worn out that the war of attrition changed again into a mobile war and the Allied forces (France, the UK, the USA, etc.) could push back the German army and win the war.

Will this happen also in the Ukrainian-Russian War? I’ll not predict how it will develop, but understanding the phenomenon of attrition war and a historical comparison can help us understand what is going on. During WW1 the Allied countries succeeded to effectively blockade Germany and to stop the import of most goods it needed. Some goods could be replaced by inland products, but most could not. This boycott was a major contribution to the Allied victory. The German try to blockade the Allied countries was not successful.

Now the present war. Being a large country, Russia has many resources, although a big part of the population is certainly not behind this war. Ukraine is weaker, but it is militarily and economically supported by the Western countries. Moreover, the Western countries try to reduce the Russian resources by an economic boycott; though as yet the result of this boycott is meagre. However, the West is and will not be prepared to send troops, and since Ukraine is much smaller than Russia, its human resources may become exhausted.

In WW1, both parties tried to destruct the infrastructure of the other, but then the means to do so hardly existed. Now, with some success Russia tries to destroy the Ukrainian infrastructure by direct attacks, while Ukraine cannot break the Russian infrastructure for political and practical reasons.

Finally, I want to mention the Battle of Bakhmut. It has some similarities with the Battle of Verdun. The then commander in chief of the German army Erich von Falkenhayn got the idea that the French army would defend the town of Verdun to the extreme, when attacked. For the French, defending the town would be a matter of prestige, but it would exhaust the French army, so Falkenhayn. And indeed, when Verdun was attacked in February 1916, the French defended the town. The defence was a military success, but the battle lasted till the end of the year and the French suffered 370,000 casualties (dead, wounded, missed). The French army was almost exhausted. But also the German army was, and with 330,000 casualties it had to pay a high price as well. Probably, this battle has contributed to the German defeat. In the present Battle of Bakhmut we see something like this. However, Bakhmut is not attacked by the Russian army in order to exhaust Ukraine, but because it needs a victory, after the many losses since the start of the war. From a military point of view, it would not be really necessary for the Ukrainian army to defend the town, but the idea is that by letting the Russians attack, the latter will lead a lot of losses, and that a massive loss of life can lead to political unrest in Russia. However, also the Ukrainian army pays dearly. What the balance of this battle will be cannot yet be said.

Soon after its start it became clear that the Ukrainian-Russian war would not be a Blitz Krieg. After a year, the war seems to have become a war of attrition. Attrition wars are usually long-lasting. The death toll is high, both of soldiers and of civilians. The costs are enormous. There is much destruction – both direct military destruction and economic destruction. There are also indirect losses of civilian lives. Once the war ended, the impact on the nations involved will be long-lasting. It can lead to political destabilization. Etc. Is it worth it?